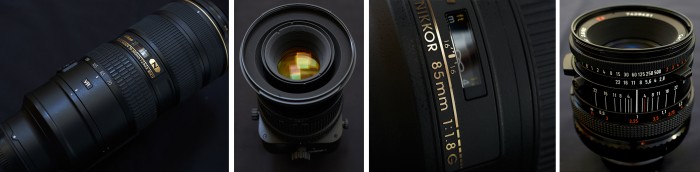

From left to right: Nikon AF-S 70-200 f/2.8 G ED VR II, Nikon AF-S 85 f/1.8 G, Nikon PC-E 85 f/2.8 Micro, Hasselblad Zeiss CF 80 f/2.8 Planar T* mounted on a Photodiox adapter.

Fighting hard against GAS (Gear Acquisition Syndrome), I still have four ways to arrive at 85 mm focal length. I may therefore check out some widespread myths about lenses: 1) Prime lenses are better than zooms. 2) Vintage lenses are ill suited for digital sensors because they are not telecentric, that is, the ray angles at the edges of the sensor exceed the acceptance angle of the microlenses, which results in reduction of color saturation, and color fringes. 3) The 35 mm lenses have a better resolution than medium and large-format lenses, simply because they need to cover only a smaller caputure area and can therefore be made from more expensive glass.

The contestants

- Nikon AF-S 70-200 f/2.8 G ED VR II

- Nikon AF-S 85 f/1.8 G

- Nikon PC-E 85 f/2.8 Micro

- Hasselblad Zeiss CF 80 f/2.8 Planar T* mounted on a Photodiox adapter

I hated the Nikon AFS 70-200 f/2.8 and the Canon equivalent, because having set up my large format camera, I was more than once harassed by photographers carrying these lenses. Considering their form factor it does not need much to imagine what some guys are compensating for.

However, by experience with the other two lenses of the “holy trinity”, i.e., the 14-24 f/2.8 and the 24-70 f/2.8, I finally completed the set. And indeed, the 70-200 f/2.8 VR II has become my preferred lens for portraits. The autofocus is quick and snappy, and the out of focus rendering (bokeh) is smooth for apertures smaller than f/3.6. At minimum focus distance the angle of view corresponds to about 150 mm only, so you cannot get the magnification of a true 200 mm. It seems that this is the price to pay for the 1.4 m minimum focal distance. Using this lens, my preferred settings for headshots are a distance of about 2 m, and 180 mm focal length at f/5.6. The vibration reduction comes in handy for the occasional handheld shot at 1/400 of a second, avoiding ISO settings above 400. You read this right, the recipocal of two times the focal length is the bare minimum for the D800, even with the VR II.

The lens is made in Japan and built like the proverbial tank. Similar to the other two professional zoom lenses, it required no calibration on my D800E. The solid tripod collar allows a quick change from portrait to landscape when the lens is mounted on a tripod or monopod, which I always recommend for this focal length.

The 85 f/1.8 G is an impressively sharp optics. It is contrasty even wide open, although (or because of) the small number of internal elements; 9 elements in 9 groups with respect to 21 elements in the 70-200 mm zoom lens. It has no aspherical elements, ED (extra low dispersion) glass, or any of the fancy coatings. This results in a low price and low weight, which is good for travel and mountaineering. Low distortion is an advantage for stitching images if a wider angle of view is desired. One can bear with the plastic majestic feel because of the relatively large glass elements. For portraiture, this lens gives you about an extra aperture and a less aggressive appearance than the 70-200 zoom. However, to say that 85 mm or 105 mm are “the” focal lengths for portraiture is an old wives’ tale*; a cropped headshot at 85 mm will bring you as close as 60 cm (23″) to the model. I definitely prefer a larger distance.

* Although this is often said and written, the perspective has noting to do with focal length, tele lenses are not compressing the scene. It is the subject-to-camera distance that changes the perspective: capture a scene with a tele lens. Use a wide-angle lens from the same viewpoint, crop the image in postprocessing to the same angle of view and you will see no difference, except a loss in image quality.

The PC-E 85 f/2.8D ED Micro is a simple optic with 6 elements in 5 groups, well built, although not quite as solid as the pro-zooms. In Nikon parlance PC-E stands for perspective control (shift) featuring an electromagnetic diaphragm, which stops down automatically or with a button instead of a lever; but this also implies that the lens can be used only wide open when mounted on a non-electronic camera or bellows.

I will not have the space to discuss the tilt and shift operations here, but the lens is very easy to use if you have experience with a view camera. There is a slight exposure shift when the lens is heavily tilted, but I would not consider this a problem when shooting digital. And yes, it will mount on the D800, unlike some reviews on the web suggest. The shift is more than generous but expect chromatic aberrations at the far end. The tilt is even too generous for landscape photography; the tilt mechanism should have a lower gear to allow more precise movement. The lens is often criticized for having the tilt and shift on orthogonal planes. I have not found this to be limiting, as landscapes require tilt but no shift (except for stitching horizontally) and architecture often requires rise but no tilt. The maximum reproduction ratio is 1:2, which is at the limit of macro/micro, but very good for tight head and product shots.

The Carl Zeiss CF 80 f/2.8 T* is the standard lens for the V-series Hasselblad film cameras; a fast (for medium format) normal prime, which is equivalent to a 50 mm lens on a full frame DSLR. These days possible the best bang for the buck; used they run at 500-600 US $ but are often sold as kit lenses to the V-series cameras. The lens mounts snugly on the Nikon body using a Fotodiox adapter (add another 80 US $). There is no electronic coupling of course, so the lens must be stopped down manually. Correct exposure can be achieved with the aperture priority setting though.

The haptics and tactility lets you believe that the lens would survive reentry from orbit, the focus ring has a small thread pitch for very precise adjustment and turns smoothly with just enough resistance to stay put.The excuse for flimsy focus rings is the reduction of the moment of inertia as a prerequisite for the ultrasonic auto-focus motors. But then, the Nikon PC-Es are manual focus lenses also, and their focus rings are a far cry from that of the Zeiss, so all this seems to indicate a mere cost cutting.

The lens has a built–in leaf shutter. Apart from shake–free operation when mirror lockup is used, it also allows flash syncronization at all shutter speeds up to 1/500 of a second. Unfortunately the lens cannot be cocked when it is separated from the Hasselblad body and the diaphragm cannot be closed manually. So the leaf shutter operation is excluded when the D800E is used as a digital back.

The test criteria

The best conceived test is useless if the methodology is not sound and the criteria are not clearly defined. But more importantly, any test will be highly subjective with inherent, strongly weighted objectives. So let’s review the criteria listed in decreasing importance.

- Corner to corner resolution at f/5.6

- Center resolution at f/2.8

- Quality of the out-of-focus areas (bokeh)

- Micro-contrast

- Macro-contrast and flare

- Chromatic aberrations

- Focus breathing

- Geometric distortion

- Vignetting

Corner to corner resolution at the working apertures (f/5.6 – f/8) for landscapes is obviously an important objective. Call me a pixel peeper, but as I have discussed here, a 23” print from even a 36 MP file requires a high pixel acuity for the uprezzing. Edge/corner sharpness wide open, on the other hand, comes second or third, although one can take this as an indicator of the lens’s overall quality. It is not difficult to design an f/5.6 kit lens with decent performance across the frame, but it is a challenge to obtain the same resolution at f/1.4.

Fast portrait lenses are used to separate the main subject from the background so the rendering of the out-of-focus points of light is an important aspect. It is, however, difficult to define smooth bokeh, pleasing to the eye; you know it when you see it. Nervousness in the transition, the shape (round or polygonal) of background highlights, and their outlining and filling are some criteria.

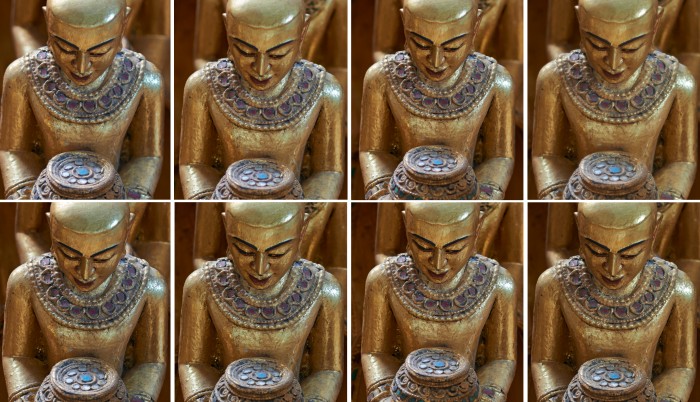

Center resolution (100% crops): Nikon 70-200, PC-E, f/1.8, Zeiss (from left to right). Aperture f/2.8 (top), f/5.6 (bottom). Click to enlarge.

Micro contrast is defined as the resolving power of fine detail structures, which are spatially close and similar in luminance. Macro contrast is the overall contrast, i.e., the recorded luminance between brightest and darkest areas of the frame. Dependent on the coatings of the individual elements, internal reflections and stray light (flare) will affect both macro and micro-contrast. Flare resistance is especially important when shooting into the light. There is also a reason why lenses come with shades; they have role to play on the lens, not in the bag.

Lateral chromatic aberration is a type of distortion in which a lens fails to focus all colors to the same convergence point. This is caused by the varying refractive indices as a function of the light’s wavelength and manifests itself by spectral separation in the form of color fringes in high-contrast areas. If this happens in non-coinciding focal planes you can notice halos of different colors; magenta in front of the focus point and green beyond. This is known as longitudinal chromatic aberration or bokeh fringing. Truly apochromatic lenses do not show longitudinal aberrations but these lenses are very rare. Unlike transverse (lateral) chromatic aberrations, the longitudinal chromatic aberrations cannot be fixed easily in post processing.

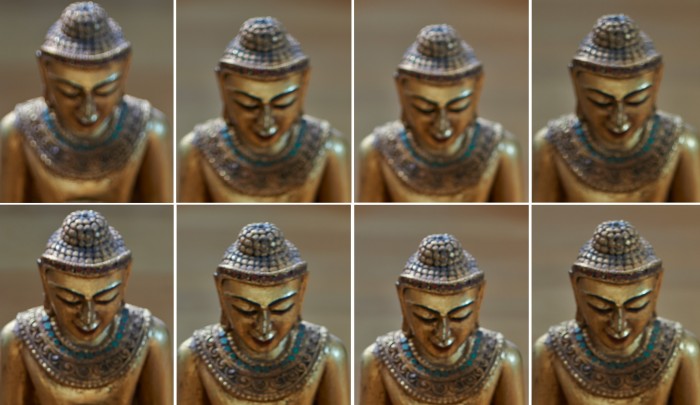

Out of focus rendering (100% crops): Nikon 70-200, PC-E, f/1.8, Zeiss (from left to right). Aperture f/2.8 (top), f/5.6 (bottom). Click to enlarge.

Focus breathing refers to the shifting of the view angle of a lens when changing the focus. The 70-200 zoom lens is a good/bad example. Although its labeled maximum focal length at infinity is 200 mm, the magnification at minim focus distance is equivalent to about 150 mm. The very expensive video and cine lenses are designed to minimize this effect since it noticeably changes the composition of the shot when racking the focus. In principle, focus breathing is a no problem in still photography as the image can easily be recomposed, something that is not always possible in a video sequence. However, focus breathing it is a nuisance when focus stacking is desired in view of the optimal aperture being limited to f/5.6 to f/8 due to diffraction.

Geometric distortions are the cause that straight lines on the subject are not rendered as straight lines on the sensor plane. Some geometrical distortions, such as barrel (often found in extremely wide angle lenses) and pincushion are easier to correct than moustache, which are a fourth order mixture of both. Strong distortions are also a nuisance for stitching more than two images together; chances are that the transformations in Photoshop pile up on the edge of the image, resulting in a considerable loss of image quality.

I consider vignetting, i.e., the reduction of the image brightness toward the corners, to be the least of the optical errors, because it can be easily corrected for in post processing; within limits, of course, to avoid noise in the shadow areas.

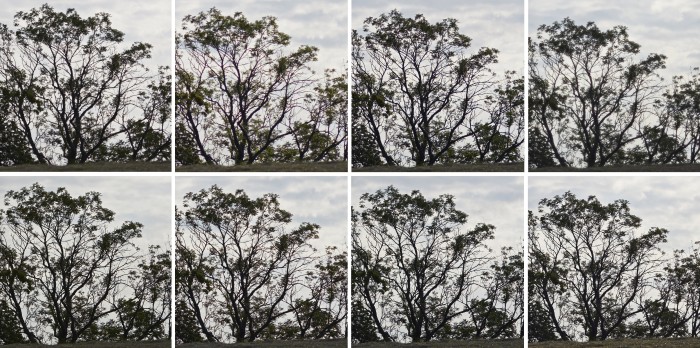

Edge resolution and chromatic aberations (100% crops): Nikon 70-200, PC-E, f/1.8, Zeiss (from left to right). Aperture f/2.8 (top), f/5.6 (bottom). Click to enlarge.

The verdict

The lenses are all capable of producing bitingly sharp results when stopped down to f/5.6. Vignetting and geometrical distortions are well under control of all lenses.

However, there are also a few weaknesses. The Zeiss and the Nikon PC-E lenses show a dreamy characteristic at f/2.8, i.e., a loss of sharpness and contrast. Whether this is a bug or a feature may be a matter of application – portrait photographers will like it whereas landscape photographers probably won’t. But then, who shoots landscapes wide open or portraits using manual focus lenses?

The Nikon AF-S 70-200 VR II is a very good lens that delivers excellent sharpness above f/4. Surprising for a zoom, the chromatic aberrations are the lowest of the bunch; I would say on par with the Zeiss. The bokeh is a bit nervous wide open but smooth at f/5.6 where it compares well with the primes. Flare is also very well controlled, which is remarkable for a lens with this large amount of glass.

The Nikkor AF-S 85mm f/1.8 G is an excellent lens that performs on a very high level in almost any regard. Sharpness is excellent, bokeh is smooth, and the borders and corners deliver very good resolution at f/2.8 and excellent sharpness at f/4. It is surprising how Nikon could achieve this without ED glass and any of the fancy coatings. There is the lowest focus breathing to boot, which comes handy for cinematography.

Ghosting and flare: Nikon 70-200, PC-E, f/1.8, Zeiss (from left to right). Aperture f/2.8 (top), f/5.6 (bottom). Click to enlarge.

The Zeiss shows the best haptics and tactility of all lenses; almost zero chromatic aberration and distortion, excellent sharpness across the frame at f/5.6 and punchy micro contrast. However, at f/2.8 the Zeiss is the underperformer when it comes to flare. The best lens in this respect is the PC-E followed by the 70-200 mm zoom.

The sensor in a DSLR reflects a lot more light than film does, so reflections from the sensor repeated by the back of the rear lens element can be significant on lenses that are not designed for digital sensors. The Zeiss lens is therefore best mounted on a Hasselblad V-series film camera for which it was originally designed; that the engineers at Zeiss know how to design lenses has been proven by the Otus, among others.

However, the question arises if it makes sense to invest into a digital back, such as the Hasselblad CFV-50, in order to replace the film magazin and give a second life to the vintage camera bodies and lenses.

In summary, prime lenses are not necessarily better than zooms, except that they offer you about the same performance at a one stop larger aperture; of course if depth of field is not a hard contraint. Having used large-format lenses of fixed focal length almost exclusively for the last 20 years, I enjoy composing with the zoom ring rather than the feet (and in this way ending up in the middle of the road).

The Zeiss 80 mm Planar proofs that vintage lenses for medium forma cameras (covering a much larger area than the 24 x 36 mm) can yield excellent results on digital cameras. Due to the large coverage they are almost telecentic on the sensor area. However, there are limits when it comes to flare, in particular at large aperture. Due to the large image circle a considerable amount of light is bouncing back on forward in the adapter and mirror box.

The haptics and tactility of these vintage lenses is not to be underestimated; it is just such a please to use them. And probably this makes you go out and shoot more.

One Comment

Thanks for a great comparision. I have 2 of these lenses and thinking to get Tilt shift PC-E next… great article. J