If all your equipment were stolen, the insurance settlement was generous, and you had to start all over, what would you procure? This question is not too academic, because it happened to a friend who had bought my Nikon D800e with the 70-200 f/2.8 VR-II as well as some other bits and pieces. All bygone.

What is the best all-purpose camera in 2017, with the right balance of image quality, versatility, and handling? One may argue that instead of learning to handle a new camera, it’s better to go out and shoot. And this is why I wouldn’t be tempted to change systems, unless this enlarged considerably the shooting envelope on grounds of resolution, dynamic range, high-ISO performance, and image stabilization. But if everything was stolen?

I wrote here that I was impressed by the Olympus OM-D Mk II for street photography. I also know a number of photographers who speak highly about their move from DSLRs to the Fuji X series, but who would openly admit to having taken a wrong decision?

Let’s check out the Olympus OM-D Mk II and Fuji X-T2, with the Nikon D810 as a reference. The “kit” lenses are the Olympus M. Zuiko 12-40 f/2.8 Pro (24-80 mm FF equiv.) the Fujinon XF 16-55 f/2.8 LM WR (24-82.5 mm FF equiv.) and the Nikkor 24-70 f/2.8 G, that is, the older, non-stabilized version. Thus, none of these lenses has vibration reduction, but considering potential problems with lens alignment in the long term, this may even be an advantage.

Aperture 2.8 on an m4/3 and APS-C size sensor is not equal to f/2.8 on 35 mm, full frame (FF). I don’t intend to go too deep into the equivalence discussion, but briefly, the depth-of-field at f/2.8 on m4/3 is roughly the same as f/5.6 on full frame, for the same angle of view and subject distance. If the images were to look the same in terms of depth-of-field and framing, and you cannot use a tripod to accommodate longer exposure times (or you have moving subjects), the ISO setting* would need to be adjusted to produce similarly bright images. However, the same noise level will result for the small and large sensors because the ISO setting amplifies the noise together with the signal. This condition of equal field of view, equal depth-of-field, equal aperture diameter, and equal exposure time is known as equivalence.

For that matter, smaller sensors do not have a depth-of-field advantage. We might, of course, compare the depth-of-field of sensors receiving the same photometric exposure, that is, at a fixed f-number, the sensors operate at the same ISO setting. The ratio of depths-of-field would then be equal to the crop factor between the sensors.

But larger sensors allow smaller apertures before the diffraction airy disk becomes larger than the circle of confusion that is determined by the print size (images from larger sensors do not have to be enlarged as much to achieve the same print). The diffraction-limited aperture for the D810 is f/9.2, while it is f/6 for the m4/3 format. Consequently, the diffraction-limited pixel size (defined as the pixel size when the airy disk becomes the limiting factor in total resolution, not the pixel density) increases for larger sensors and for the same depth-of-field. In other words, the diffraction-limited depth-of-field is the same for all sensor sizes.

So where is the advantage of the larger sensor? As we have about the double number of pixels and four times the surface area (comparing the best 35 mm FF to m4/3) we obtain a larger signal to noise ratio if we were not limited by the photometric exposure, i.e., we can choose longer exposure times using a tripod or because the scene is bright enough. At the same time, we have a larger discrete oversampling, which allows a more subtle sharpening and noise reduction when the file is printed at the same output size.

A larger sensor (even with the same or smaller pixel size) will have lower apparent noise for a given print size, because noise in the higher resolution camera gets enlarged less, even if the image looks noisier at 100% on the screen. And for all that has been said, the lenses must keep up with the increasing pixel densities. A 25 mm lens at f/2.8 for m4/3 must have twice the resolving power, as a 50 mm lens at f/5.6, to keep everything in a linear relation. More precisely, the same MTF (modulation transfer function) at double the line pairs per mm (lp/mm). It’s not that easy, however, because a higher pixel density still yields more detailed images even with the same lens; you just lose in micro-contrast. Then, computational imaging (focus stacking) and tilt-shift lenses allow for the circumvention of the diffraction limitations of larger sensors.

And the advantage of the smaller sensor? The larger the pixel count, the more severe shot discipline is required to make best use of the sensor’s capabilities (albeit not at the same final print size). I have written about this before; the D810 is particularly demanding: tripod mount, mirror up and exposure delay, and contrast detection auto-focus or magnified live-view manual focusing. And there is the obvious size, weight, and cost issue, the mirrorless systems setting you back by about 2.4k CHF, $, Euros. Add 1k for the Nikon outfit if you can get a phase-out discount.

We could have used the Olympus and Fuji prime-lens offerings and compared them to the reference Zeiss 55 or 28 f/1.4 Otus lenses on the D810. But this would be an unfair fight not only because of the price and weight, but because the appeal of the m4/3 and APS-C systems is the versatility and weight saving for the normal zoom range. And this is why we haven’t included the Sony Alpha 7R II in the shootout; their matching lenses, particularly the G master series, are just as big. Indeed, a Nikon D750 with the Nikkor 24-120 mm f/4 lens would have been a better match in terms of price and weight (1420 g wet), but that’s not what I had sitting in the cupboard.

The Olympus OM-D II is loaded with tons of features that have been discussed in various forums; so here only those that I consider most relevant: 5 axes in-body stabilization, Focus Bracketing that allows recording up to 999 frames for focus stacking, high-resolution sensor shift technology, built in Wi-Fi, auto-focus fine tune compensation of individual lenses, touch-screen with trackpad functionality for selecting the focus point, my strongly preferred 4/3 aspect ratio of the 20 MP sensor (11 micro-meter-square pixel area), 60 fps burst rate with the electronic shutter, and minimum exposure time of 1/8000 sec. The sensor and processor also support 4K movies in frame rates up to 30 p or Full HD up to 1080 p.

The Fuji X-trans cameras are praised for their color rendition and film simulation modes, although I do not care much about in-camera processing (smiling cat scene mode, anybody?) and would prefer to clean up the menu structure. The camera is not as feature loaded as the Olympus, but what is not to like about the retro-style aperture ring, exposure setting, and ISO-dial. In this way the main settings can always be checked even with the camera switched off or when it sits on a tripod.

The Fuji X-T2 is quipped with a 24.3 MP APS-C sensor (pixel area 15 micrometers square) and allows image capture at up to 8 fps with full AF tracking or at up to 14 fps using the electronic shutter. Various frame rates are available for video, up to 60 p for Full HD recording and 30 p for UHD 4K. And there is built-in Wi-Fi to boot. I cannot comment more on the video capabilities because I am not a video shooter; the results from the D810 are not that motivating.

The Fuji also has a focus lever joystick that allows for rapidly adjusting and changing the selected AF point or area, but (grumble) its position on the body is too low to be handled comfortably.

The Sony sensor (36 MP, full frame 24×36 mm, 24 micrometers per square pixel) and matching camera electronics, leading to a high image quality, still make the D810 one of the best 35 mm offerings, albeit requiring a high level of shot discipline. Feature-wise, the D810 shows its age: no in-body stabilization, no focus peaking, no tilt screen, no Wi-Fi, and no focus joystick. However, Nikon is the only camera in the test that has a built-in flash unit as part of Nikon’s creative lighting system. The other two cameras come with a small hot-shoe flash unit though.

I didn’t mention the electronic viewfinder in this list, because the optical prism viewfinder has its advantages regarding auto-focusing in low light and battery life (confirmed – and by a large margin with the Fuji being the worst). The battery life is not to be underestimated; when I trekked the Annapurna circuit in 2015, an avalanche had taken away the entire infrastructure to the upper Manang valley. Refraining from shimping and limiting live-view to the bare minimum, I was able to survive for 10 days with only two batteries. This is still impossible with mirrorless cameras**.

But sometimes I wouldn’t mind a lighter option for the outdoors (or when I go places that are not primarily dedicated to creating images and an iPhone may be too much of a compromise when an opportunity arrises), a less obstructive option for street and reportage, and better image stabilization when a tripod is not allowed. For comparison, the Olympus weighs 574 g (wet) + 382 g for the lens, the Fuji combo weighs 507 + 310 g, and the Nikon 880 + 900 g.

Writing about handling is inevitably biased, depending on the camera system you are used to. There is reluctance to change, and when swapping systems one expects to be familiar as fast as possible, without even reading the manual (which was indeed required when I bought my first Nikon DSLR).

Coming from Nikon, it took us about an hour to figure out the basics of both cameras, consulting the handbooks once or twice per model, before we were able to go shoot. But after another hour of using the three cameras in turn, we both increasingly reached for the Olympus, the main reasons being its deeper grip, the less front-heavy lens, and the better electronic viewfinder (although they both have the same 2.36 Mdots resolution).

The lens shade of the Zuiko is partially made of metal and has a snug fit. Sometimes these details matter. The front dial around the shutter is a bit awkward, though. Its default function in aperture priority setting is the exposure compensation, but it’s far too easy to turn accidentally. And we preferred the Fuji concept (pivot) of the LCD screen; the Olympus (swivel) is more versatile for selfies (I don’t care) and for images like the above. But the mechanism clashes with most of the L-plates for tripod mounting. With the OM-D, you must learn to use the left hand to turn the camera off, as every other camera has its power switch on the right side of the body.

At the risk of upsetting the mirrorless fanboys, I still wouldn’t like to peek into a screen for hours while the camera drains the battery. EVFs still have another disadvantage; they are too bright in dark situations, ruining your night vision, while washing out the colors in bright situations. So the depth-of-field preview, contrast preview, and color preview must be prefixed with “sort of”. And the colors of the Fuji EVF are outright ugly. When we turned to the Nikon, we both felt some relief looking through an optical finder. There is an aspect to like about them though: the live histogram and the instantaneous playback mode with blinkies that allow for a quick check without removing the eye from the viewfinder. The image in the EVF looks two-dimensional, which isn’t necessarily bad, as it corresponds more to the final image, just like live-view on the LCD screen. The best in this respect is of course the iPad which is just like composing on the ground glass of a large format camera.

Changing lenses, the sensors in mirrorless bodies are exposed to the elements, and I know the mess caused by salt spray, and sand raining through the roofs at Kolmanskop. Good to know that all three camera and lens combos are dust and splash resistant. Mind you, weather-sealing (just like professional grade) is a catchword that is nowhere defined. A huge advantage of mirrorless is the option of complete silence, which is highly appreciated in quite a number of situations.

The three systems prove that the weight and size advantage comes from the smaller sensor and lenses, not from suppressing the mirror box. I hope that the D820, or whatever it will be, will come with higher resolution and at least as good dynamic range and per-pixel quality as the current model; and Nikon, please add an EVF option for the hot shoe; this would seal the deal.

The Fuji is not as nice in person as in the images. It’s not very comfortable to hold if you have large hands (the loaner was equipped with a thumb rest), and the lens is front heavy even though it is the lightest in the test. It handles better with the battery grip, but then its haptics form factor reminds me very much of a classical DSLR.

The most impressive, single feature in the three camera systems is the 5-axis, in-body stabilization of the Olympus OM-D; one can obtain critically sharp images at 12 mm for exposures of up to half a second and at 35 mm (70 mm equiv.) for up to 1/10 th of a second, which is well below the 1/f (equivalence) rule that isn’t even sufficient for the D810. So you are looking at ISO 200 instead of 3200 for an equivalent depth-of-field. This system is also the basis for the high-resolution mode, where the camera takes 8 images with the sensor shifted by half a pixel pitch and combines them into an 80 MP RAW file.

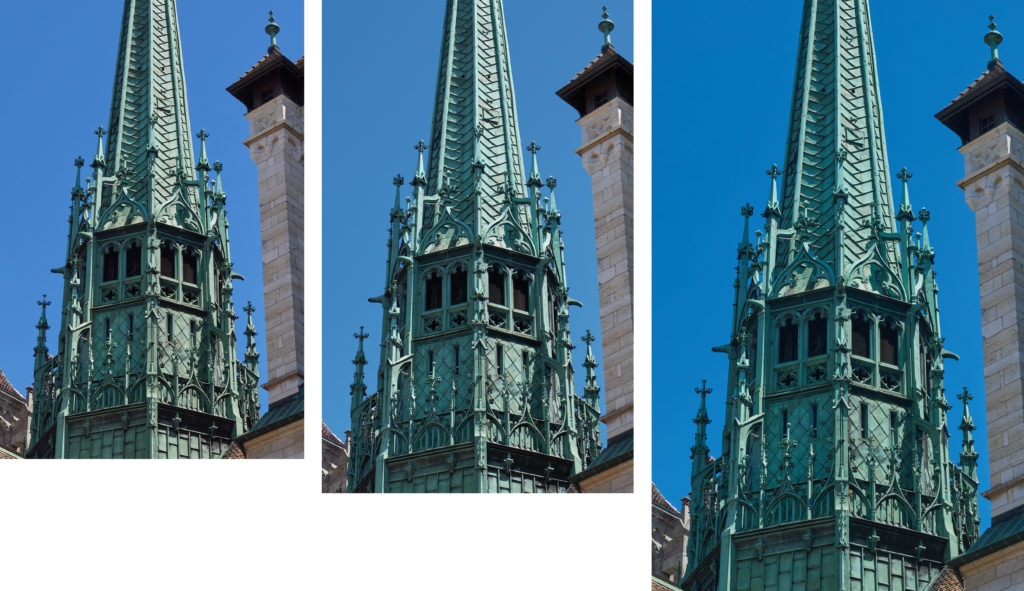

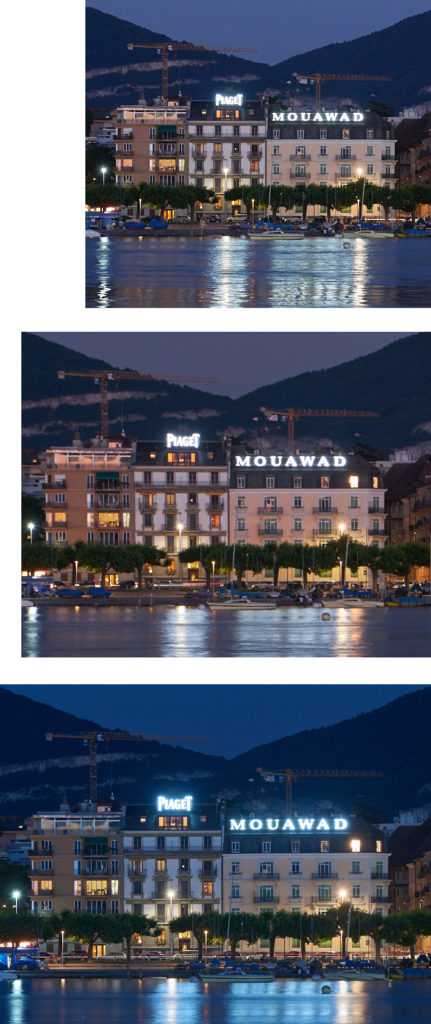

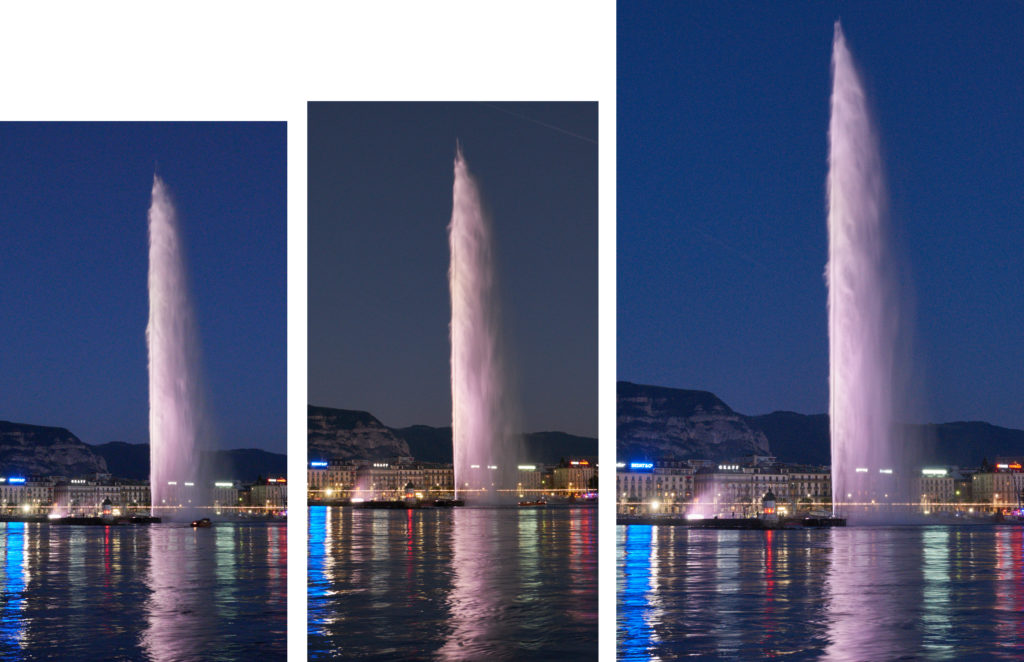

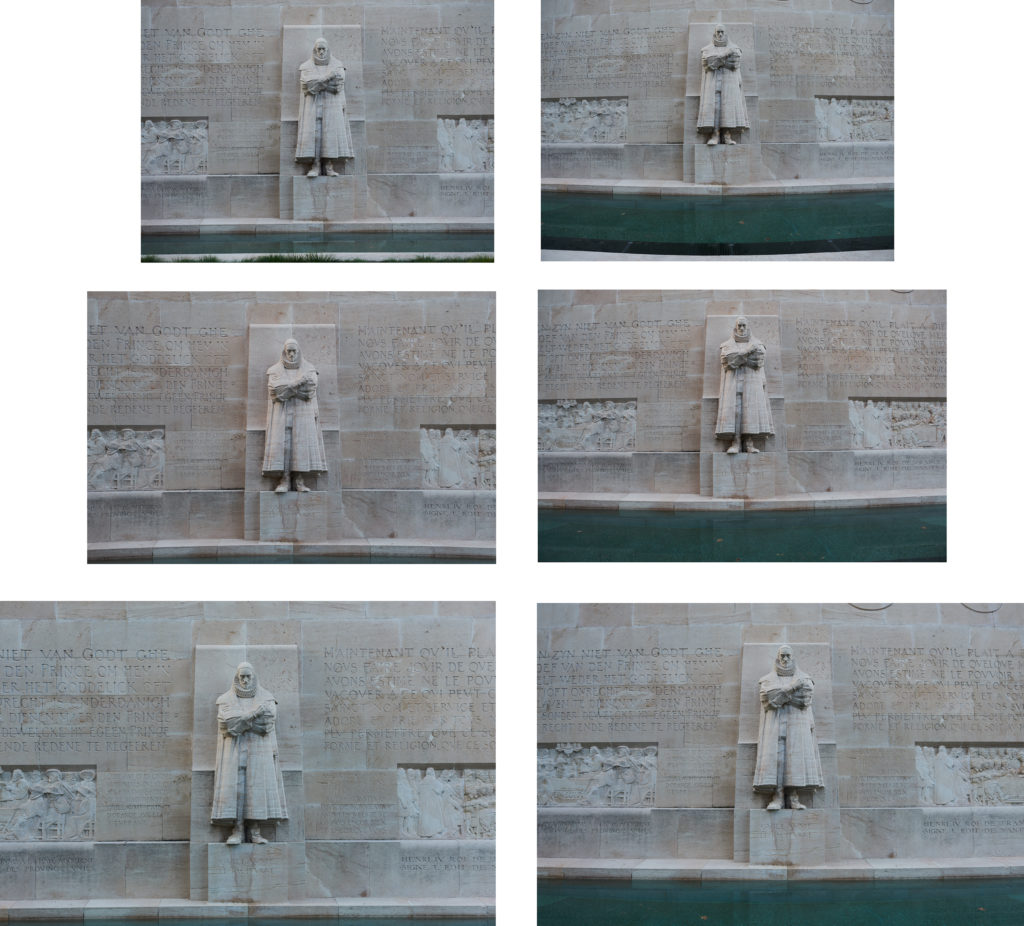

The first set of tests was conducted under “normal” shooting conditions, handheld travel and reportage style work under unfavourable, harsh mid-day sunlight. The dynamic range of the m4/3 sensor impresses; the measured two-stop difference with respect to the D810 doesn’t really impinge on real-world shooting situations. Resolution and highlight roll off is surprisingly good for such a small sensor, and I would be more than happy if this sensor/electronics architecture were scaled to 80 MP in a full-frame body. There must be another technical limitation that I am not knowledgeable about: why are medium-format cameras so slow. Reading out 60×20 MP/s should make it possible to read out 10×100 MP/s, but we are far from that. On the other hand, if your image sucks at 10 fps it sucks twice at 20 fps.

For the second set of tests we exerted the usual shot discipline, heavy tripod, magnified live view to check focus, 3 seconds shutter delay, optimal shooting aperture below the diffraction limit, base ISO. All images were processed in CaptureOne Pro 10 with identical settings. Note that the pre-sets differ, that is, more aggressive sharpening and default distortion/vignette correction in case of the Fuji and Olympus.

Out of camera, the Olympus’ white-balance is a bit cooler, and its exposure is a tad higher. The Fuji’s images are slightly red, and the Nikon produces a greenish hue. After correction, the colors are much the same as the example of the fruit basket shows.

Images are useful up to ISO 1600 or thereabouts, but rely on heavy noise reduction in the RAW processor. I first thought to give an edge to the Fuji, the color noise looking more film-grain-like; see the above image at 100 or 200%. But checking the EXIF data revealed that the ISO 1600 setting on the Fuji corresponds to ISO 1000 on the two other cameras. I had used aperture priority setting and tripod mount and thus didn’t notice that the camera chose a longer exposure time corresponding to about 2/3 of an aperture.

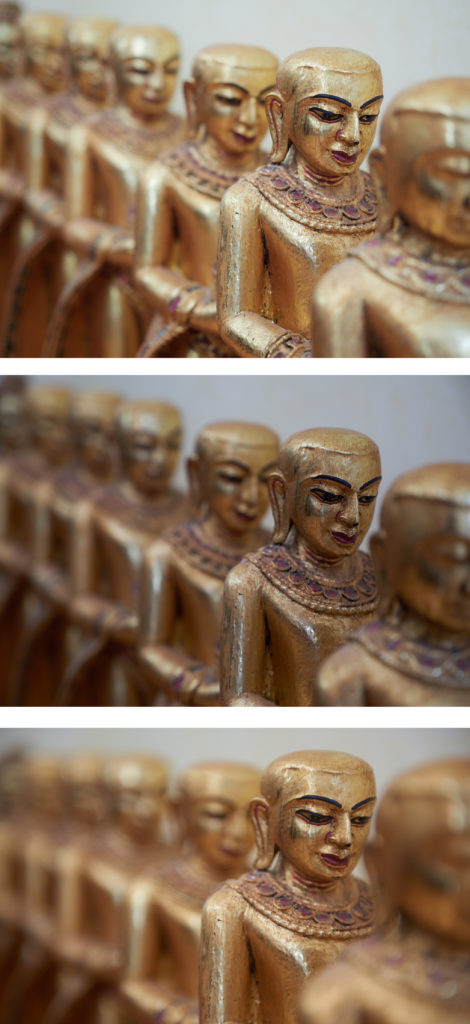

The small sensors are not for the shallow depth-of-field diehards, as the row of Buddhas shows. This is, btw, a good example where face detection and continuous autofocus is a nuisance for the back-button shooter; the cameras couldn’t make up their mind about the most important face to focus on. I see another small advantage of Fuji’s autofocus system here, and it hunts less in the dark. None of the standard zoom lenses are really bokehlitious; nothing beats the portrait primes and long, full-frame teles. Therefore, bokeh is the (hyped up) benefit of full frame, although I don’t care too much about it, except for head-shot portraits. In particular, I find out-of-focus foregrounds rather disturbing.

Distortion is a weak point of the lenses for the mirrorless bodies, as the lens designers seem to rely on software correction, in-camera, or with the supported RAW converters. Disabling the distortion correction reveals massive barrel distortion at the wide end. The next step beyond this is a fish-eye lens, really. For the Zuiko lens, distortion is no more relevant at 25 mm, while it turns into light pincushion distortion at 40 mm. The Fuji behaves similarly, but its pincushion distortion at 55 mm adds insult to injury. All lenses were well aligned and centered, so nothing to complain about.

The Zuiko is incredibly sharp (high contrast and high resolution) throughout the zoom range. Because of its exceptional border and corner performance is also digests the distortion correction without too much visible impact. The resolution in the center does not improve by stopping down, but degrades visibly from aperture f/8 when diffraction starts to kick in.

The Fujinon lens’ sweet spot is the 16 mm setting, from which the quality drops steadily toward the long end. At 55 mm, one needs to stop down a little to bring up the corners, while the center never really shines (and this leaves you with a very narrow range of usable apertures, basically f/3.5 to f/5.6).

There is one important point to consider: the Zuiko 12-40 f/2.8 Pro is as good as it gets, none of the m4/3 primes really outperforms this lens, while there are some very competent Fujinon primes that are clearly better than the tested zoom. This is even more true for Nikon’s F mount.

I would rate the limit for a fine print*** at A3+ for the mirrorless options, while the Nikon files can be printed one size up, to about A2. There is some considerable in-camera, RAW file cooking by Olympus, which results in a loss of tonality in uprezzed prints. Therefore, consider stitching or the high-resolution mode if the subject allows.

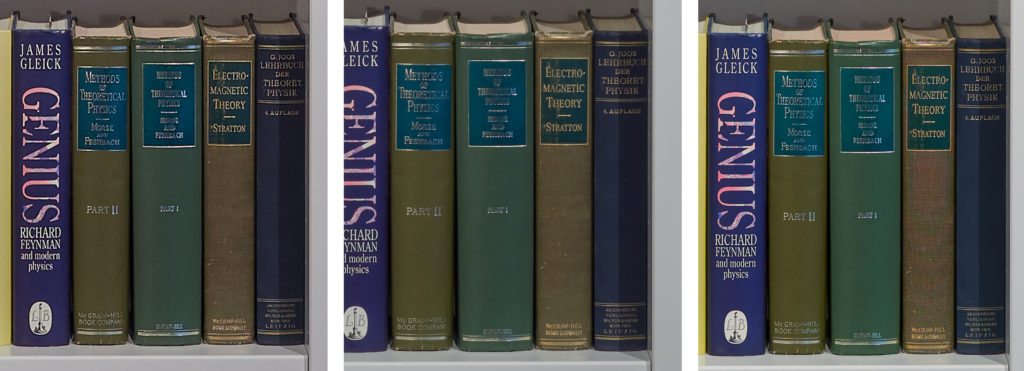

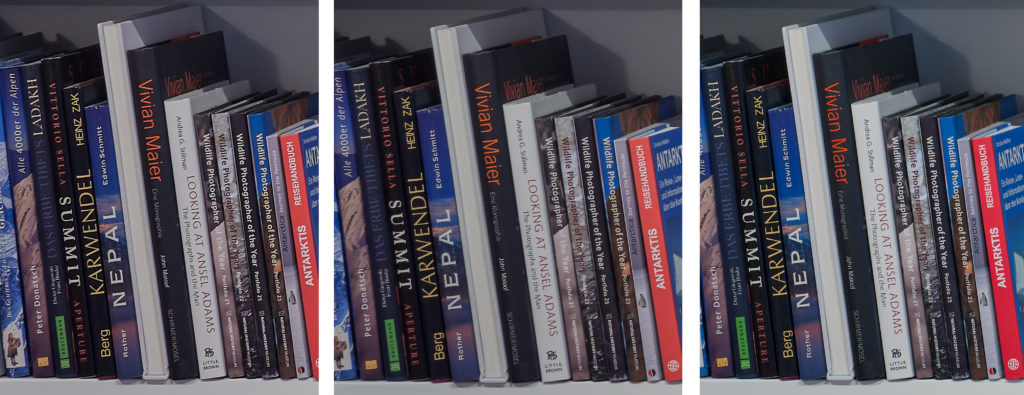

In the high-resolution mode, the OM-D takes eight images and generates a RAW composite of impressive 80 MP. You will need a sturdy support, an optimal aperture, and a shutter delay. Moreover, you will be limited to subjects that remain completely static during the about one-second capture period. The images are less sharp on the pixel level (the lens just not having the resolving power), but the digital oversampling allows for more subtle sharpening and a more organic look in large (A2) prints. But as the bookshelf examples show, any field curvature or sharpness fall-off in the lens is revealed without mercy.

When everything comes together for landscape and architecture, and you can bring the tripod, the Nikon excels, which is no surprise. But the Olympus holds its own in terms of image quality, in particular, dynamic range and high-ISO. Under low light shooting conditions, we get more usable (albeit not perfect) results from the Olympus than from any of the other systems. Considering its form factor, solid build, legendary weather sealing, in-body image stabilization, and high-res mode, it’s a no-brainer and has been my friend’s choice.

And the Fuji? We just didn’t fall in love with it. There is no “singular sales proposition” except for being mirrorless. It’s a fine camera, but it’s priced in the ballpark of an FF Nikon D750 or Canon EOS 6D and frankly not that much lighter. But the shootout also shows that it’s not an unfair fight. The advantages of the larger sensors are subtle (if you exclude bokeh), something I had noticed comparing the D800e to medium format.

Myself, I consider the OM-D as a street and travel combo and a backup body****. It’s no easy decision given the camera’s heavy price tag. I could economize by selling the Nikkor 24-70 f2.8 G that I never loved, but used in those situations where I could go with one body and lens only. Or I wait for a similar Nikon offering.

But life is short. SR

*Note that ISO does not change the camera’s sensitivity, which is fixed by the quantum efficiency of the sensors. The ISO setting simply defines a post-sensor gain applied to the signal. In this way, ISO defines the range of light that is being digitized. Above a certain ISO value, where the images become sensor read noise limited and not downstream electronics limited, the cameras are said to be “ISO invariant.” In this region, increasing ISO has no benefit to image quality. You could also adjust the image in post processing. The graphs here show that you can set the Nikon D810 to ISO 250 before you use up the additional highlight headroom (of about 2 apertures) to the level of the Olympus at base ISO. So, for the same photometric exposure (and same depths of field), both cameras behave more or less in the same way.

** I found a “display off” function on the Fuji but not on the Olympus – but don’t take my word for it; check. Not sure by how much this will increase battery life though.

*** As a side note, I never bought the concept of normal viewing distance, which implies that larger prints are viewed from further away (usually between 1.5 to 2 times the diagonal of the print) and therefore require less resolution. While this may be true for a billboard seen from a highway, people will move closer to an exhibition print in a gallery or private home, as long as there is more detail to be resolved. Consequently, a print that looks OK at normal viewing distance but falls apart when moving closer doesn’t qualify for me. There is a clearly visible lack of tonality and color separation once you go below 300 ppi, particularly on glossy paper.

**** Adapting lenses from other formats and flange focal distances is often not a good idea. It also has to do with the ray angles and thickness of the lens cover glass. Whether it makes sense to combine the OM-D body with my Nikon tele lenses would need to be tested.